The article below was published in The New York Times, by JULIET MACUR & NATE SCHWEBER.

HOURS AFTER SUNSET, the cars pulled up, one after another, bringing dozens of teenagers from several nearby high schools to an end-of-summer party in August in a neighborhood here just off the main drag.

For some of the teenagers, it would be one last big night out before they left this decaying steel town, bound for college.

For others, it was a way to cap off a summer of socializing before school started in less than two weeks. For the lucky ones on the Steubenville High School football team, it would be the start of another season of possible glory as stars in this football-crazy county.

Some in the crowd, which would grow to close to 50 people, arrived with beer. Those who did not were met by cases of it and a makeshift bar of vodka, rum and whiskey, all for the taking, no identification needed. In a matter of no time, many of the partygoers — many of them were high school athletes — were imbibing from red plastic cups inside the home of a volunteer football coach at Steubenville High at what would be the first of several parties that night.

“Huge party!!! Banger!!!!” Trent Mays, a sophomore quarterback on Steubenville’s team, posted on Twitter, referring to one of the bashes that evening.

By sunrise, though, some people in and around Steubenville had gotten word that the night of fun on Aug. 11 might have taken a grim turn, and that members of the Steubenville High football team might have been involved. Twitter posts, videos and photographs circulated by some who attended the nightlong set of parties suggested that an unconscious girl had been sexually assaulted over several hours while others watched. She even might have been urinated on.

In one photograph posted on Instagram by a Steubenville High football player, the girl, who was from across the Ohio River in Weirton, W.Va., is shown looking unresponsive as two boys carry her by her wrists and ankles. Twitter users wrote the words “rape” and “drunk girl” in their posts.

Rumors of a possible crime spread, and people, often with little reliable information, quickly took sides. Some residents and others on social media blamed the girl, saying she put the football team in a bad light and put herself in a position to be violated. Others supported the girl, saying she was a victim of what they believed was a hero-worshiping culture built around football players who think they can do no wrong.

On Aug. 22, the possible crime made local news when the police came forward with details: two standout Steubenville football players — Mays, 16, from Bloomingdale, Ohio, and Ma’lik Richmond, 16, from Steubenville — were arrested and later charged with raping a 16-year-old girl and kidnapping her by taking her to several parties while she was too drunk to resist.

The case is not the first time a high school football team has been entangled in accusations of sexual assault. But the situation in Steubenville has another layer to it that separates it from many others: It is a sexual assault accusation in the age of social media, when teenagers are capturing much of their lives on their camera phones — even repugnant, possibly criminal behavior, as they did in Steubenville in August — and then posting it on the Web, like a graphic, public diary.

Within days of the possible sexual assault, an online personality who often blogs about crime zeroed in on those public comments and photographs and injected herself into the story, complicating it and igniting ire in the community. She posted the information on her site and wrote online that the police and town officials were giving the football players special treatment.

The city’s police chief begged for witnesses to come forward, but received little response. In time, the county prosecutor and the judge in charge of handling crimes by juveniles recused themselves from the case because they had ties to the football team.

“It’s a very, very small community here,” said Jefferson County Juvenile Judge Samuel W. Kerr, who recused himself. His granddaughter dated one of the football players initially linked to the incident. “Everybody knows everybody.”

After more than two months in jail, they are under house arrest on rape charges, awaiting a trial that has been set for Feb. 13. Mays, a star wrestler, also faces a charge of disseminating nude photographs of a minor. The kidnapping charges were dropped.

The parents of the boys, who declined requests for extended interviews, said that the boys were innocent. The boys’ lawyers assert that the boys have been tried unfairly online, and vow they will be exonerated when all the facts are known.

The case has entangled dozens of people in and out of this town.

Three Steubenville High School athletes became witnesses for the prosecution and testified against Mays and Richmond, their friends, at a probable cause hearing in October. The crime blogger and more than a dozen people who posted comments on her Web site have been sued by a Steubenville football player and his parents for defamation. The girl’s mother, in several brief interviews last month, said her family had received threats, so extra police have been patrolling her neighborhood.

“The thing I found most disturbing about this is that there were other people around when this was going on,” Steubenville Police Chief William McCafferty said of the events that unfolded. “Nobody had the morals to say, ‘Hey, stop it, that isn’t right.’

“If you could charge people for not being decent human beings, a lot of people could have been charged that night.”

A Bright Spot in Steubenville

Steubenville is an industrial city in Appalachia — locals love to note it is hometown to the Rat Pack crooner Dean Martin, the porn actress Traci Lords and the oddsmaker Jimmy Snyder, known as Jimmy the Greek. The city once was teeming with so much gambling, prostitution and organized crime that Steubenville was given the nickname Sin City. But now the downtown is a skeleton of its former self: though the Steubenville visitors center sells life-size cutouts of Dean Martin and “Dino Lives!” T-shirts, many stores are abandoned, boarded up long ago.

The Grand Theater, once a lavish Art Deco movie house, last showed a film in 1979. Around the corner, Denmark’s women’s clothing store is now a graveyard for discarded hangers and broken clothing racks. In the window of the store is a dusty Woman’s Home Companion magazine from 1948, just about the time Steubenville began its long and painful turn for the worse.

The steel mills that used to employ thousands and draw people here have all but ground to a halt, and the once-plentiful jobs in the coal mines are dwindling. The lack of jobs scared off residents at such a frenzied pace that Steubenville had by far the steepest decline in population of any metropolitan area in Ohio from 1970 through 2000, according to a study by Ohio State University.

And among those who have stayed — about 18,400 in Steubenville — many are struggling. The median household income is $33,188, about a third lower than the national figure. More than one quarter of the residents are living below the poverty level. Also, the police say the city’s drug problems are growing, with heroin addiction the latest vice. In recent decades, new residents arrived from Chicago, bringing “Chicago-style violence,” like drive-by shootings in the tough parts of town, said McCafferty, the police chief.

Despite all those components to this depressed city, a bright light remains for the people here: the Steubenville Big Red football team.

The team recorded its first season in 1900 and quickly became a legend in Ohio high school football. It has won nine state championships, including back-to-back undefeated seasons in 2005 and 2006.

Some former players call it a highlight of their lives to play at Harding Stadium, a gleaming shrine to football also called Death Valley. The stands seat 10,000, more than half the town’s population, and the home side is packed every game, sometimes so packed that it is standing room only. Tailgating in nearby parking lots usually begins about 9 a.m. for a 7:30 p.m. game. Several years ago, Halloween trick-or-treating was postponed because it fell on game day.

Inside the stadium, a big thrill for fans is seeing a sculpture of a rearing red stallion called Man O’War shoot a six-foot flame from its mouth, marking each time Big Red scores.

The team’s Web site declares that Big Red is “Keeping Steubenville on the map.” That is probably true.

“Everybody around here goes to games on Friday nights, and I mean everybody — people come for miles,” said Jim Flanagan, 48, who grew up in the area. “It’s basically the small-town effect. People live and die based on Big Red because they usually win and it makes everybody feel good about themselves when times are tough.”

But emphatic pride over high school athletes, Flanagan said, has turned into something that can feel ugly.

“The players are considered heroes, and that’s pretty pathetic, because they’ve been able to get away with things for years because of it,” Flanagan said. “Everyone just looks the other way.” A Night Takes a Grim Turn

Just before 10 a.m. on Aug. 11, fans who are part of what is called the Big Red Nation poured into Harding Stadium clad in the team’s colors, red and black, to see Big Red’s second scrimmage of the season and to get a sense of how the team would fare this year.

What they saw were two players who stood out from the rest: Mays and Richmond.

Mays, who hails from a nearby town and who went to Steubenville High because of its successful football and wrestling programs, showed off his strong arm at quarterback. Richmond, who the police say came from a troubled home and has lived in Steubenville with guardians since he was 8, dominated as a quick and tall wide receiver. He also was a star of the Big Red basketball and track teams.

The two athletes gave hope to fans that Big Red might be headed back to the top.

Of Mays, one person at the time wrote on JJHuddle.com, a Web site for Ohio high school sports, “If he has the composure, could be very enjoyable to watch that young man grow up with Ma’lik.” Mays and Richmond helped Big Red prevail that day in the scrimmage, before heading off to a night of parties.

Across the river, in a well-kept two-story colonial house in a solidly middle-class West Virginia neighborhood, the 16-year-old girl told her parents that she was going to a sleepover at a friend’s house that night. She then headed off to those parties, too.

She is not a Steubenville High student; she attended a smaller, religion-based school, where she was an honor student and an athlete.

At the parties, the girl had so much to drink that she was unable to recall much from that night, and nothing past midnight, the police said. The girl began drinking early on, according to an account that the police pieced together from witnesses, including two of the three Steubenville High athletes who testified in court in October. By 10 or 10:30 that night, it was clear that the dark-haired teenager was drunk because she was stumbling and slurring her words, witnesses testified.

Some people at the party taunted her, chanted and cheered as a Steubenville High baseball player dared bystanders to urinate on her, one witness testified.

About two hours later, the girl left the party with several Big Red football players, including Mays and Richmond, witnesses said. They stayed only briefly at a second party before leaving for their third party of the night. Two witnesses testified that the girl needed help walking. One testified that she was carried out of the house by Mays and Richmond while she “was sleeping.”

She woke up long enough to vomit in the street, a witness said, and she remained there alone for several minutes with her top off. Another witness said Mays and Richmond were holding her hair back.

Afterward, they headed to the home of one football player who has now become a witness for the prosecution. That player told the police that he was in the back seat of his Volkswagen Jetta with Mays and the girl when Mays proceeded to flash the girl’s breasts and penetrate her with his fingers, while the player videotaped it on his phone. The player, who shared the video with at least one person, testified that he videotaped Mays and the girl “because he was being stupid, not making the right choices.” He said he later deleted the recording.

The girl “was just sitting there, not really doing anything,” the player testified. “She was kind of talking, but I couldn’t make out the words that she was saying.”

At that third party, the girl could not walk on her own and vomited several times before toppling onto her side, several witnesses testified. Mays then tried to coerce the girl into giving him oral sex, but the girl was unresponsive, according to the player who videotaped Mays and the girl.

The player said he did not try to stop it because “at the time, no one really saw it as being forceful.”

At one point, the girl was on the ground, naked, unmoving and silent, according to two witnesses who testified. Mays, they said, had exposed himself while he was right next to her.

Richmond was behind her, with his hands between her legs, penetrating her with his fingers, a witness said.

“I tried to tell Trent to stop it,” another athlete, who was Mays’s best friend, testified. “You know, I told him, ‘Just wait — wait till she wakes up if you’re going to do any of this stuff. Don’t do anything you’re going to regret.’ ”

He said Mays answered: “It’s all right. Don’t worry.”

That boy took a photograph of what Mays and Richmond were doing to the girl. He explained in court how he wanted her to know what had happened to her, but he deleted it from his phone, he testified, after showing it to several people.

The girl slept on a couch in the basement of that home that night, with Mays alongside her before he took a spot on the floor.

When she awoke, she was unaware of what had happened to her, she has told her parents and the police. But by then, the story of her night was already unfolding on the Internet, on Twitter and via text messages. Compromising and explicit photographs of her were posted and shared.

Within a day, a family member in town shared with the girl’s parents more disturbing visuals: a photograph posted on Instagram of their daughter who looked passed out at a party and a YouTube video of a former Steubenville baseball player talking about a rape. That former player, who graduated earlier this year, also posted on Twitter, “Song of the night is definitely Rape Me by Nirvana,” and “Some people deserve to be peed on,” which was reshared on Twitter by several people, including Mays.

The parents then notified the police and took their daughter to a hospital. At 1:38 a.m. on Aug. 14, the girl’s parents walked into the Steubenville police station with a flash drive with photographs from online, Twitter posts and the video on it. It was all the evidence the girl’s parents had, leaving the police with the task of filling in the details of what had happened that night. The police said the case was challenging partly because too much time had passed since the suspected rape. By then, the girl had taken at least one shower and might have washed away evidence, said McCafferty, the police chief. He added that it also was too late for toxicology tests to determine if she had been drugged.

“My daughter learned about what had happened to her that night by reading the story about it in the local newspaper,” the girl’s mother said.

“How would you like to go through that as a mother, seeing your daughter, who is your entire world, treated like that?” the mother said. “It was devastating for all of us.”

Mays and Richmond were arrested Aug. 22, about a week after the girl’s parents reported the suspected rape.

Taking Sides on Blogs

Alexandria Goddard, a 45-year-old Web analyst who once lived in Steubenville and writes about national crime on a blog, heard about the case early on and rushed to investigate it herself. She told The Cleveland Plain Dealer in September that she did so because she had little faith that the authorities would do a thorough job.

Before many of the partygoers could delete their posts, photographs or videos, she took screen shots of them, posting them on her site, Prinniefied.com. On Aug. 24, just after the arrests, she wrote on her site that it was “a slam dunk case” because, she said, Mays and Richmond videotaped and photographed their crime and then posted those images on the Web. Goddard pressed her case.

“What normal person would even consider that posting the brutal rape of a young girl is something that should be shared with their peers?” she wrote. “Do they think because they are Big Red players that the rules don’t apply to them?”

She cited by name several current and former Steubenville athletes, accusing them of having a criminal role in the suspected assault by failing to stop it and then disseminating photographs of it. According to court documents, Goddard responded to a comment that read, “Students by day …gang rape participants by night” by writing that the football coach should be ashamed of letting players linked to the incident remain on the field. In another post, she added, “Why aren’t more kids in jail. They all knew.”

Of the Big Red athletes who were with Mays and Richmond that night, she said: “No, you are not stars. You are criminals who are walking around right now on borrowed time.”

Anonymous commenters on her blog took aim at Steubenville High, its football coaching staff and the local police for not disciplining more players or making more arrests in connection with the rape accusation. On another site, Change.org, a person started a petition demanding that the school and the coach publicly apologize to the girl. The petition also asked that the Steubenville schools superintendent admit that there was a “rape culture and excessive adulation of male athletes” at Steubenville High.

In a day, 100 people signed the petition, and 169 signed before no more signatures were accepted.

Around town, the discussion of what might have happened that night in August raged, growing more heated by the day. The accusations on Goddard’s blog, posted by Goddard and others, sparked more debate. The local newspaper, The Herald-Star, ran a letter to the editor from Joe Scalise, a Steubenville resident, who criticized the blogger’s site, saying it “has lent itself to character assassination and has begun to resemble a lynch mob.”

Even without much official public information about the night, some people in town are skeptical of the police account, like Nate Hubbard, a Big Red volunteer coach.

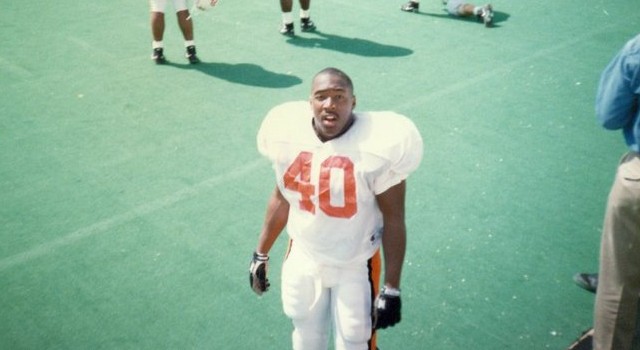

As he stood in the shadow of Harding Stadium, where he once dazzled the crowd with his runs, Hubbard gave voice to some of the popular, if harsh, suspicions.

“The rape was just an excuse, I think,” said the 27-year-old Hubbard, who is No. 2 on the Big Red’s career rushing list.

“What else are you going to tell your parents when you come home drunk like that and after a night like that?” said Hubbard, who is one of the team’s 19 coaches. “She had to make up something. Now people are trying to blow up our football program because of it.”

There is no shortage of people who feel the opposite. They absolutely accept the account of sexual assault, and are weary of what they call the protection and indulgence afforded the football team. That said, more than a dozen people interviewed last month who were critical of the football team and its protected status, real or perceived, did not want their names used in connection with comments about the team, for fear of retribution from Big Red football fans.

One man said he wanted to see the accused boys go to prison, but insisted he remain anonymous because he did not want his house to be a target for vandalism.

Bill Miller, a painter who played for Big Red in the 1980s, said the coach was to blame because he was too lenient with players regarding bad behavior off the field.

“There’s a set of rules that don’t apply to everybody,” he said of what he called the favoritism regarding the players. “This has been happening since the early ’80s; this is nothing new. It’s disgusting. I can’t stand it. The culture is not what it should be. It’s not clean.”

Others attacked Goddard, the crime blogger, for her commentary regarding what she called the town’s twisted football culture and its special treatment of football players, including a player who is suing her for defamation. As part of the legal action against her by the player and his family, the court has allowed the family’s lawyers to seek the identities of those people who disparaged the player by name on the blog. The player has not been charged with any crime.

Goddard, who has not been located by the court so it can serve her with a copy of the complaint, did not respond to an e-mailed request for comment. She remains active on her blog.

Goddard’s lawyers, Thomas G. Haren and Jeffrey M. Nye, said that their client was a journalist whose work was protected by the First Amendment.

“This case strikes at the heart of the freedom of speech and of the press,” they said in a statement. “We intend to see those constitutional guarantees vindicated at the end of the day.”

Seeking Evidence

Despite the seeming abundance of material online regarding the night of the suspected rape and the number of teenagers who were at the parties that night, the police still have had trouble establishing what anyone might regard as an airtight case.

A medical examination at a hospital more than one day after the parties did not reveal any evidence, like semen, that might have supported an accusation of rape, the police said. The Steubenville police knocked on doors of the people thought to be at the parties, but not many people were forthcoming with information. In several instances, the police seized cellphones so they could look for photographs or videos related to the case.

Eventually, 15 phones and 2 iPads were confiscated and analyzed by a cyber crime expert at the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Investigation. That expert could not retrieve deleted photographs and videos on most of the phones.

In the end, the expert recovered two naked photographs of the girl. One photograph showed the girl face down on the floor at one party, naked with her arms tucked beneath her, according to testimony given at a hearing in October. The other photograph was not described. Both photographs were found on Mays’s iPhone. No photograph or video showed anyone involved in a sexual act with the girl.

Anonymous complaints and chatter on the Internet about a less than fully aggressive investigation have perhaps not surprisingly proliferated.

It has left McCafferty, the police chief, fuming and frustrated.

For weeks after the girl’s parents came forward, he again pleaded to the other partygoers to come forward with information about the possible sexual assault. Only one did, he said.

“Everybody on those Web sites kept saying stuff that wasn’t true and saying, why wasn’t this person arrested, why aren’t the police doing anything about it,” he said. “Everybody wanted to incriminate more of the football players, some because some of the other schools in the area are simply jealous of Big Red.”

McCafferty, who has been the police chief for 11 years, is sensitive when it comes to criticism of his police force. He took over in the wake of a United States Department of Justice inquiry into the Steubenville Police Department’s patterns of false arrests and excessive force. And he now goes out of his way to try to assure residents that they can trust the police department again.

He said it bothered him when he heard people say that Big Red players got away with crimes in town. If crimes are being committed, he said, they are not being reported. He said no one had ever given him a concrete example of players’ receiving special treatment.

In 23 years on the force, he said, he can only remember one player before Mays and Richmond being arrested; that player was convicted of assault.

“It’s always, ‘They said players are getting away with things,’ but when I ask who ‘they’ is, no one can tell me,” McCafferty said.

Standing by His Players

In this part of the football-obsessed Ohio Valley — where at least several houses in every neighborhood have a “Roll Red Roll” or a “Big Red” sign out front — everybody knows Coach Reno Saccoccia. He has coached two generations of players at Big Red and has won 3 state titles and 85 percent of his games, according to the team’s Web site. The football team’s field is named Reno Field.

This season, the coach, who is used to winning, had to do without Mays and Richmond. But others who were at the parties and might have witnessed the suspected assault continued to play on the team. Saccoccia, a 63-year-old who brims with bravado, was the sole person in charge of determining whether any players would be punished.

Saccoccia, pronounced SOCK-otch, told the principal and school superintendent that the players who posted online photographs and comments about the girl the night of the parties said they did not think they had done anything wrong. Because of that, he said, he had no basis for benching those players.

The two players who testified at a hearing in early October to determine if there was enough evidence to continue the case were eventually suspended from the team. That came eight games into the 10-game regular season.

Approached in November to be interviewed about the case, Saccoccia said he did not “do the Internet,” so he had not seen the comments and photographs posted online from that night. When asked again about the players involved and why he chose not to discipline them, he became agitated.

“You made me mad now,” he said, throwing in several expletives as he walked from the high school to his car.

Nearly nose to nose with a reporter, he growled: “You’re going to get yours. And if you don’t get yours, somebody close to you will.”

Shawn Crosier, the principal of Steubenville High, and Michael McVey, the superintendent of Steubenville schools, said they entrusted Saccoccia with determining whether any players should be disciplined for what they might have done or saw the night of Aug. 11. Neither Crosier nor McVey spoke to any students about the events of that summer night, they said, because they were satisfied that Saccoccia would handle it.

In an interview last month, Crosier maintained that he was not aware of what might have happened to the girl, even with all of the talk in the town, until three Big Red athletes testified in early October. At the same time, he said that he might have read the online petition that called for a public apology from the players and the team. He said that if he had, he had not thought much of it.

McVey said he was not aware of the team having any off-field issues before this one.

“If this happened as a pattern, it would have set off an alarm,” McVey said of the possible sexual assault. “But we think this was an isolated incident.”

Neither Mays nor Richmond had a record, the police said, and each had numerous community members testify as character witnesses for them at the hearing in which the judge determined they should be tried as juveniles, not as adults.

Saccoccia was one of those witnesses, as was Michael Haney, the school’s varsity basketball coach, who said Richmond was such a talented player that he ranked in the top 100 high school players in the state.

Yet the football season went on without Mays and Richmond, two of the team’s stars. And Big Red’s record reflected the gap in its roster.

The team finished the season 9-3 after losing in the second round of the playoffs. It was the end of a disappointing year for the program and the fans who expect so much from Big Red players.

The fans from a perennial rival, the Massillon Tigers, took advantage of the team’s legal troubles and taunted players.

In the Tigers’ cheering section at the game against Steubenville was one fan who painted on his chest the words, “Rape Big Red.”

Players and Families Wait

Big Red’s season ended in early November, and the daily conversation in town is less and less about the suspected rape than it is about how the team will perform next year.

But inside a courtroom at the county jail, less than two miles down a hill from the football stadium, the debate over what happened to the girl that summer night is still unfolding.

The hearings in the case are open to the public, but court documents regarding the matter are sealed because the defendants are juveniles. Mays and Richmond were released to their families or guardians last month, though they must wear electronic monitoring devices and are allowed to leave home only to attend school at the county jail or church. On school days, they head to classes at the jail, wearing their new uniform: green sweat pants and tan shirts, which have numbers on their left sleeves.

Last month, Mays’s father, Brian, declined to be interviewed, saying, “It’ll all work out.” From the street outside his house, two shelves filled with athletic trophies could be seen inside a second-story room.

Richmond’s father, Nate, said his son was innocent. In September, he camped outside the county jail next to a banner that read, “Set my people free.”

“He didn’t do anything,” Richmond said.

Ma’lik Richmond now lives with his legal guardians, Jennifer and Greg Agresta, in a middle-class neighborhood with neatly trimmed lawns. A basketball hoop sits on the street in front of his house. Greg Agresta is a member of the school board.

Richmond’s grandmother, Mae, said the charges surprised her because Ma’lik had been so focused on sports and school, with hopes of leaving Steubenville for a better life and having a better life than his father, who has served time in prison and been charged with many crimes, including manslaughter.

“Me and Coach Reno was talking, and he said Ma’lik was just in the wrong place at the wrong time,” she said.

Adam Nemann, Mays’s lawyer, said the case was unusual because the police collected no physical evidence or testimony from the girl who asserts she was raped.

“The whole question is consent,” he said. “Was she conscious enough to give consent or not? We think she was. She gave out the pass code to her phone after the sexual assault was said to have occurred.”

Walter Madison, Richmond’s lawyer, said his client was already at a marked disadvantage because so many people discussed the incident online, through blogs and on Twitter.

“It’s an uphill battle because you’ve got social media going on and people formulating opinions, people who weren’t there and don’t know what happened,” he said. “In a small community, it exponentially snowballs out of control. I think the scales are a bit unbalanced.”

He said that online photographs and posts could ultimately be “a gift” for his client’s case because the girl, before that night in August, had posted provocative comments and photographs on her Twitter page over time. He added that those online posts demonstrated that she was sexually active and showed that she was “clearly engaged in at-risk behavior.”

The lawyers for the boys also said the three athletes who testified against their clients had credibility issues. The lawyers said that the police had found nude photographs of women on the phone of one of the witnesses, and that two witnesses had admitted recording some aspect of the suspected assault. Those alone could be crimes, the lawyers said, but the witnesses were given immunity from prosecution. Their testimony, the lawyers suggested, might have been given in a bid for leniency.

The special prosecutors on the case, Marianne Hemmeter and Jennifer Brumby of the Ohio Attorney General’s Crimes Against Children unit, declined to comment because the investigation was open.

But in court, they have rejected the defense’s claims. The girl, they have said, was in no condition to give consent to sexual advances that night — and the teenagers there knew it, the prosecutors said.

At a hearing in early October, prosecutors told the judge in the case that the defendants treated the girl “like a toy” and “the bottom line is we don’t have to prove that she said ‘no,’ we just have to prove that when they’re doing things to her, she’s not moving. She’s not responsive, and the evidence is consistent and clear.”

At a hearing last month, the girl’s mother said her daughter remained distraught and did not want to attend school. The girl’s friends have ostracized her, and parents have kept their children away from her, the mother said.

The girl does not sleep much, said the mother, who testified that she often hears her daughter crying at night.

The mother said the obsession with high school football in Steubenville is partly to blame. It shocked her that Saccoccia testified as a character witness for the defendants last month, she said.

In the courtroom that day, she remembered thinking, how dare he?

“Just Coach Reno saying he would testify for those boys, saying he was so proud of them, that speaks volumes,” she said. “All those football players are put on a pedestal over there, and it’s such a status symbol to play for Big Red, the culture is so different over there.”

The mother added: “I do feel like they’ve had preferential treatment, and it’s unreal, almost like we’re part of a TV show. It’s like a bad “CSI” episode. What those boys did was disgusting, disgusting, and for people to stand up for them, that’s disgusting, too.”