October arrives as the leaves turn a golden hue across West Virginia. The same colorful vibrant sheen of helmets worn by Bobby Bowden’s Mountaineers four decades ago.

Long before he created Chief Osceola’s flaming spear and Seminoles fans were thrilled to football greats the caliber of Ron Simmons, Deion Sanders, Charlie Ward and Chris Weinke in Doak, it was in Morgantown — not in titanic collisions with the Miami Hurricanes and Florida Gators during 34 glorious seasons in Tallahassee — where the Hall of Fame legend says he experienced perhaps his greatest high as well as the lowest depths of coaching despair.

To Bowden, his crossroad was the Backyard Brawl. Competitive intensity displayed by campuses just 76 miles apart.

“Without question, if I had to pick from all my wins — at the very top — it would be the one over Pittsburgh and Johnny Majors my last year there,” Bowden said. “The loss to Pitt my first season (1970), I don’t know if I ever got over that.”

Lovely wife Ann, who shared with Bobby 389 career victories and FSU national championships in 1993 and 1999, also experienced all 129 losses, one more stinging than all others. “That was the only time I’ve ever cried after a game.”

The tears have long subsided for both. It is homecoming this Saturday along the banks of the Monongahela River and for the first time since that glorious win over a fierce arch rival in 1975, Bobby will stand on the Mountaineers sideline. Following his departure for FSU and the fates of subsequent seasons, Bowden has never seen a game in the college town that gave him his big time start. He was 46 years old when he packed up for a warmer climate. Saturday, nearing 85, he and Ann will be celebrated as parade Grand Marshals.

As the West Virginia fight song goes, “The pride of every Mountaineer.”

“We came within inches of staying there,” Bobby remembered, emphasizing how narrow the decision was by he and Ann to take the Seminoles post. “Four of my children were in school there. Robyn, Steve, Terry and Tommy. We had to leave them behind. I’d been there 10 seasons — first as the offensive coordinator under Jim Carlen — then as the head coach. We were really making progress.”

Bowden would earn 42 wins at West Virginia, starting with his 1970 debut season at 8-3. It was an eventful stay, as WVU transitioned from the genteel Southern Conference of smaller schools to the rigorous schedule of a major independent. Surrounded geographically by the Big Ten, Southeastern Conference and ACC — not to mention Joe Paterno in his zenith at Penn State — a relentless grind to achieve seven, eight and nine win seasons left scant room for either weakness or error.

Bobby played Pac-10 teams in a quest for national exposure and dueled with eastern foes the likes of Boston College, Syracuse, Virginia Tech and archrival Pitt. This after Carlen bolted for Texas Tech following a surprising 10-1 campaign in 1969.

“Right after the bowl game that year, he came in the locker room and said he was leaving,” Bowden said. “The whole staff was surprised. I couldn’t even campaign to be the next coach. My dad was dying in a hospital in Birmingham and I had to drive to be with him. I wanted the job, but couldn’t stay and didn’t think I’d get it. Well, the school called me in Alabama and told me that the president and board had voted to make me the head coach.”

Every single season thereafter would be served on one-year contracts. Off the field, Bowden befriended Marshall University, opening his coaching offices in the wake of the unfathomable grief of the Herd’s team dying in a plane crash. He consoled a young West Virginia native and Kent State student Nick Saban on the loss of a father Bobby knew well, going so far as to offer Saban a job at West Virginia. And true to his Christian convictions, he taught Sunday school — during the season.

Head coach on Saturday. Church classroom on Sunday.

Life was far from perfect. Especially that October day in 1970 when Bowden at midseason held a commanding 35-8 halftime lead in his first Backyard Brawl as the boss. The game was in Pittsburgh where “they had no intention of coming back in the second half. Pitt went with three tight ends in the second half to slow the game down thinking we would score 60. Well we were small and Pitt went for it on every fourth down and started to get momentum.”

He let out a long breath, pausing for a moment before the memories rushed back. It has been 44 seasons.

“I went out and sat on the ball” Bowden continued. “They beat us 36-35. I was so embarrassed. I told myself that I would never do that again. Not if I scored 100 points. People accused me of running up scores at Florida State. They should have been with us that day. I coached my team from then on. And I never sat on the football a single game the rest of my career.”

A handkerchief for Ann, please.

You’ve perhaps heard the tale of Bowden being hung in effigy following a 4-7 year in 1974, racked by injuries. And of slipping on winter ice in his driveway, a reminder better weather awaited in the Sunshine State.

Yet what proved to be his final home game in Old Mountaineer Field nearly bonded him to West Virginia’s woods for life. Come this Saturday, the old grads and young lads will relive with Bowden and his returning lettermen the final frantic seconds when powerhouse Pitt was stunned by Bobby’s razzmatazz.

One of college football’s most dazzling success stories in 1975 was Johnny Majors’ Panthers. On the ascent — two years shy of the Tennessee great returning to his alma mater with then-Pitt defensive coordinator Jackie Sherrill assuming command to lead the school to a national championship — the Panthers offense featured the acclaimed Tony Dorsett.

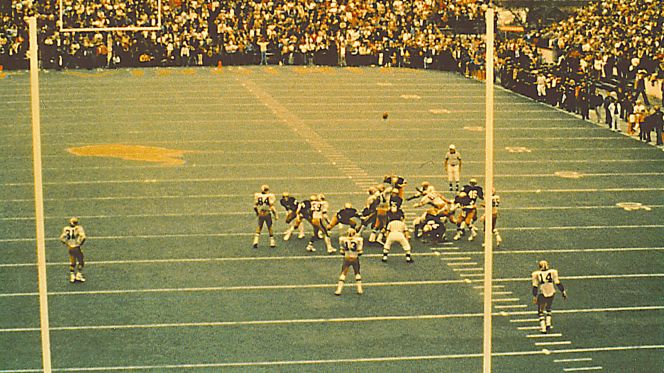

Dorsett was at all levels — in high school, collegiately and through a storied run with the Dallas Cowboys — as talented as anyone to have played the game. The future Heisman Trophy winner and Pro Football Hall of Fame immortal had been unstoppable the week before against Army and would amass a Pitt record 303 yards rushing the following week against Notre Dame. But in West Virginia’s sunken bowl, resounding with the emotion of a roaring crowd, Dorsett was targeted on every carry. These yards came at a punishing price. And even sporting All-American quarterback Matt Cavanaugh, the Panthers were on the ropes late in the 4th quarter of a 14-14 tie.

This was Bowden’s hour.

Bobby had recruited and groomed rock solid quarterback Dan Kendra. Wide receiver Danny “Lightning” Buggs played to his nickname as Bowden’s first two-time All-American. Dave Van Halanger, a Pittsburgh native and later invaluable FSU assistant coach, was a hulking Mountaineer offensive lineman, buying time and creating push. And a one-time walk-on played an important role, hauling in two passes on the day.

His name was Tommy Bowden. The future head coach of the undefeated Tulane Green Wave — and who later shared top billing in blockbuster Bowden Bowl confrontations between Clemson and Florida State — lettered as a clutch flanker.

A decade of Bobby’s football life was coming down to a few ticks of the clock.

On fourth down, backed up to its own 21-yard line — with 18 seconds to play — Pittsburgh lined up as if to go for it. The Panthers were clearly rattled.

“Johnny Majors came running onto the field and called time out,” Bowden said. “They really were going to go for it. And then they punted.”

The punt soared out of the end zone to midfield. With just 10 seconds to go, West Virginia owned the football — and hope.

“Twice before I had caught a curl pass with the tight end Randy Swinson in the flat underneath me,” Tommy remembered. “Now Randy ran a wheel route behind my curl and caught the ball down the sidelines before he stepped out with about four seconds left.

“My own father used me for bait!”

He sure did.

With the football at the 21-yard line, Bowden turned to another walk-on. A kicker named Bill McKenzie. Given all the ensuing years that would offer Wide Right and Wide Left and national titles vanishing outside the uprights, this was the height of irony. Bowden’s greatest moment was about to come off the squared toe of a blond haired conventional style specialist, from 38 yards away.

The game-winning field goal by West Virginia in the 1975 Backyard Brawl against Pittsburgh.

No kick in history was ever more authoritative. Dead. Solid. Perfect. 17-14.

“That may have been my greatest day as a coach. It was my 46th birthday. My son caught two passes. We won the Backyard Brawl. The crowd stormed the field. All of them,” marveled Bowden. “I never did get to shake Johnny Majors’ hand. I could never find him.”

He and Ann concluded their WVU stay with a Peach Bowl win later in December against North Carolina State and another Hall of Fame coach, Lou Holtz. Let the record show it was the first career postseason victory for Bowden. The first of 21, the most of any coach in history. He accepted a subsequent overture from Florida State and the rest is the well-chronicled stuff of lore, including his last hurrah in Seminole garnet and gold.

Bowdens last game was a victory that took place in the 2010 Gator Bowl — against West Virginia.

“I have always been ‘a band’ guy,” Bobby shared. “I am looking forward to the parade and all the music. I just love marching bands. On the sideline at the Gator Bowl before the game the Mountaineer band started playing the school fight song. I started getting choked up. I had tears.”

Tears, idle tears. When we look upon the happy autumn fields, thinking of the days that are no more.