Article is from Sports Illustrated, originally published on December 16th, 1968. Pictures are from Wheeling Ironmen Program.

Let us pause to consider West Virginia, Appalachia’s Vale of Kashmir, where washing machines still grace the porches of the Architecture Anonymous houses and junk jalopies still garnish the gardens. West Virginia is Mona’s Lunch, the best restaurant in Greenwood. Mona’s Lunch is the front rooms of a tongue-and-groove bungalow. Its decor is flowered wallpaper covered with Saran Wrap and No Swearing signs, its menu is creamed beef on biscuits and its clientele runs to aging permanent-waved ladies in garish pants, singing along and dancing to jukebox country and western.

Let us consider Wheeling, its wealthiest city. Wheeling has so much more to offer than it gets credit for. Where but in Greater Wheeling could you find the World’s Tallest Smokestack? (“A Landmark,” the Wheeling News-Register correctly describes it under a front-page picture of the region’s civic monument, “322 feet taller than the Eiffel Tower.”) Where but in Wheeling, and the whole lush Ohio Valley, would you find such a lavish per capita production of steel, chemicals, strip-mined coal, cement dust, smog and slag? Where but in Wheeling would you find the smallest city in the nation to support a professional football team? Where but in Wheeling could you find the Ohio Valley Ironmen of the Continental Football League?

Wheeling, clearly, is just the sort of place to clasp a minor league pro football team called the Ironmen to its rusty tin heart. And Wheeling does love its Ironmen, no mistake about that. The Ironmen have had two leagues dissolve around them and have survived a two-season-long, 18-game losing streak and, one year, rain in five of seven home dates. Yet they live on, the only minor league team in the country to have persevered in the same city under the same ownership for as long as six years.

The Ironmen are representative of the whole Continental League, football on the wrong side of the tracks. To avoid the competition of high school, college and major league football, the season begins in August and ends in November. For the same reason, most games are held Sunday evenings. The Ironmen play at the south end of Wheeling Island, formerly the swellest place in town, now a respectable residential area where beer joints are making incursions. They use a high school stadium, and the terms of their tenancy establish their status. The Ohio Valley Professional Athletic Association, Inc. rents Wheeling Island Stadium for $350 per season, and it is welcome to the premises anytime the high schools aren’t either playing or practicing.

Yet the Ironmen represent more than professional penury. In their own way they are the Packers in Green Bay, a breath of the big time in a small city, a wellspring of civic chauvinism. Quarterback Ed Chlebek makes about $74,000 less than Bart Starr, but when he walks down Main Street or Market Street in Wheeling heads turn and hands shoot out. There are friendly shouts. In the space of one block, team Publicity Man Dave Cochran—a young Irishman happy to get back to Wheeling after Air Force hitches in Mountain Home, Idaho and Thule, Greenland—can yell greetings into a men’s store where Running Back Clyde Thomas works, point out Halfback John Sykes and his pig-tailed daughters, shake hands with club Vice-President Harry Robbin and bump into Coach Lou Blumling. Expressing skepticism about the Ironmen can get you thrown out of the Embassy Restaurant or punched at Kelly Mike’s Sports Center in nearby Martins Ferry. More than a thousand fans attended one preseason training session up at West Liberty (a former NFL camp), and 500 once stood through a cold drenching rain to watch another. More than 950 Ohio Valleyans own one or more shares of Ironmen stock. When it looked as if the Ironmen would fold two years ago, whole families came to the club’s basement headquarters in tears, and little kids brought in piggy banks.

“Pride of ownership is what does it,” says Mike Valan, an industrial painting contractor who is president of the football club and who doubles as general manager to save it one salary. “There are a lot of people who are proud of living in this valley. We think we’ve got the nicest place in the world to live. Hell, we don’t think it, we know it.

“I think we serve a need. You can get anything you want in Pittsburgh, and it’s only 60 miles away. But if the average millworker wants to take his wife and family to Pittsburgh to see a Steeler game, he has to pay for gas, restaurant and maybe even motel. That runs into big money. He can get his thrills here a lot cheaper.”

But sense of ownership can sometimes get out of hand. “I get crazy phone calls at all times of night,” Valan complains. “And letters. There are always diagrams of plays we ought to use, and I suspect we should’ve fired at least 15,000 coaches. I was even attacked by a woman once. She came out of the stands, ripped my shirt and clawed me.”

The Ironmen, as is true of all Continental League teams, work on a poor man’s budget. The league allows a maximum salary of $200 per game per player, the total of the entire team’s salaries not to exceed $5,000 per game. Last year Wheeling’s budget was $270,000, and the team lost $90,000.

“It’s always tight,” Valan says. “You have to remember you’re minor league and not get caught up in big-city dreams about a third major league and television contracts with a fourth network. This year we tried to be realistic and get along with $175,000, which we cannot. But we do have our first chance to break even this season. When I say break even, I mean lose only a few thousand bucks. That’s breaking even.”

The Coach of the Ironmen, Lou Blumling, is a stubby, amiable, gravelly-voiced Dutchman who joined the team as a scout in 1962 after a career as a 150-pound scatback for West Liberty State College and as a coach in local high schools. He is paid $10,000 a year and is convinced that Continental League football is just a shade below the two big leagues.

“If you talk to the real pro fan, ” Blumling says, “he’ll tell you this is great football to watch for excitement. And we feel we hit just as hard as they do upstairs. This is just one very short step below the big time. We get big college stars, All-Americas even, who can’t make it. I can go through this NFL roster and find players on every page who got their chance here. We look at the Super Bowl last year and find two of ours who used to play for $150, Bob Brown of Green Bay and Andy Rice of Kansas City.”

The Ironmen, Blumling says, fly like the big-time teams. They use the same plane the Chicago White Sox use. They stay in Holiday Inns and they eat the same meals, even if they do go home right after the game to save money.

But there are differences, too. The Ironmen don’t have fancy equipment—no Exer-Genies, no diathermy machines. Just one seven-man blocking sled and a couple of dummies. Worse, they suffer from a severe lack of time. Most weeks the tiny coaching staff—four men, as opposed to, say, Green Bay’s 10—has only Tuesday through Thursday, 1 hours per night, to work with the players. Even if the high schools happen not to play on Friday, they aren’t particularly anxious to see the Ironmen use the facilities. “This week was Homecoming,” Blumling sympathized recently, “and they sure didn’t want us messing up their field.”

Anyway, five Ironmen players are high school coaches and can’t practice on Friday. One player commutes all the way from Uniontown, Pa. (70 miles), four from Pittsburgh and two from Columbus. Many of the others have to get up early to work. Defensive Tackle Joe Pabian, for example, shovels hot asphalt all day, starting at 7:30 a.m. (Even on Monday mornings. After one game of notorious memory the Ironmen didn’t get back to Wheeling until 6:10 a.m.)

“Suppose we tried to keep them here two, three hours a day,” Blumling says. “Here’s a kid who has to drive 70 miles home, then get up to go to work. It’s a little difficult putting demands on a kid making $150 a week. It’s easy for him to say, for this money I’m not going to put up with this. I’m not going to work my tail off.”

Quarterback-Coach Chlebek agrees. “Where Vince Lombardi can say, ‘Be here at 6,’ Lou has to finesse his way around.” In addition to the handicaps that come with the franchise, the Ironmen voluntarily assume another. Unlike the league teams such as the Norfolk Neptunes and the Orlando Panthers, which stock up with veterans and thereby remain consistent powers, the Ironmen try to use youngsters still on their way up. Sometimes this hurts them.

“Jerry Marion, our starting flanker, was called up by Pittsburgh last year,” Blumling says. “That didn’t help us, but they had to have him, and we’re not going to hold a kid down when he can go up and make a better living.

“But if we have a man hurt, where do we go to get a replacement? We have a 35-man maximum this year, but last season it was 30. That’s barely one full team, not allowing for injuries.”

Players aren’t so all-fired easy to get at the beginning of the year, either. Blumling starts out by writing almost every college in the football guide for lists of players they think might be able to play pro football. He sends each man a questionnaire. He scouts. He pores over the NFL and AFL drafts, sending a letter to just about everybody but Leroy and Orange Juice. The letters are bumble. They say, approximately, “If your other prospects somehow don’t work out, we’re still interested.”

“We have a tough time here in Wheeling,” he admits. “Take a kid who lives in California who gets an offer from Wheeling, W. Va. He’s never heard of Wheeling. Put yourself in his place. Do you go to Wheeling or do you go to Orlando, which you’ve at least heard of?”

Blumling is too much a native son to consider the possibility that the hypothetical prospect from Yorba Linda, Calif. might have heard some bad things about Wheeling or that he might just possibly not like it once he saw it, although he does parenthesize something to the effect that “a lot of great ones leave here and play somewhere else.”

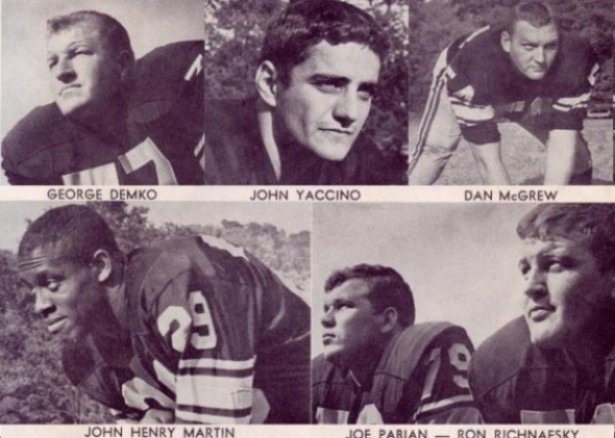

“Frankly, I wondered what I was getting into,” remembers George Demko, one of the original Ironmen and now offensive line coach. “I brought my girl down, and she said, ‘George, I just don’t know.’ ”

“Coming into Wheeling, at first, I didn’t get a fair evaluation of the city,” Chlebek says in a delicately oblique reference to the strip mines and slag dumps. “The coal and all, you know. And it doesn’t have those beaches like Orlando. Orlando had 25 fullbacks to pick from this year. If we have three or four we’re fortunate. It’s difficult for Coach Blumling. But he can tell them we’ve sent more players to major teams than anyone else, and that’s a big, big selling point. And the people here are really friendly. It’s a good place to live.”

Darryl Lesser, 23, 240-pound starting offensive tackle from Washburn University, is a good case in point. Darryl first tried out for a Canadian team on the word that there would be only 25 Americans in camp. (The league quota is 13 per team.) When he arrived he found 35 American rookies alone, and the veterans hadn’t even checked in yet. Lesser played very well in the first intra-squad game. The next day he was cut.

“Man, I was down,” he remembers. “I was determined to go back to Topeka and help out my father in his business. I felt I had kind of let my brother down. He had been working for my father all the while I’d been in college. When Lou Blumling called, I didn’t want to come to Wheeling at all. It had been hard enough to face people in Topeka after getting cut in Canada. It would have been even worse not making the Ironmen.

“Then, when I flew in here and saw it, I tell you. Besides, there wasn’t anybody to meet me at the airport like they said there would. There wasn’t hardly anybody to even run the airport. I called Coach Snyder [Bob Snyder, Blumling’s predecessor], and he said to ‘hop on the next limousine when it came out’ in a couple of hours or so. Finally, I got a ride. When I came down that one stretch of road, I thought, ‘This is it?’ All that coal and industry. It wasn’t like Kansas.”

“When I got to Coach Blumling and the others,” Lesser adds, however, “people couldn’t have been nicer. People with the team have been great to us.”

Part of the reason is that Lesser, like other young Ironmen, is dedicated to his work. When he got married, he picked the day carefully. “It had to be a Monday,” he says, “because that’s the only day we don’t have practice or a game coming up.” Right after a game Lesser and his parents drove 500 miles in continuous rain to Stamford, Texas. An hour before the wedding Darryl was still getting licenses and shots for flu. “I missed Tuesday practice,” he admits. “I apologized to the coach.”

Jim Cunningham, a veteran of three years in the NFL with the Redskins, the Ironmen’s entire reinforcement corps at all three linebacker positions, is another case. “We drove through Wheeling once when I was still with Washington and saw signs for the Ironmen,” he says. “My wife said, ‘This’ll probably be your next stop.’ I said, ‘If I have to come down here, I might as well be in my grave.’

“Well, they opened up my eyes real quick. The only thing these boys lack is timing. They may actually hit harder in this league because they want to make a name for themselves.

“It’s a big change from the NFL in another way. There we might go over 130 plays for each game, maybe 12 different audibles. Here they just don’t have the time. I have to commute from Union-town, so I only practice one day a week—Thursday, defense night.”

Unlike his players, Lou Blumling devotes seven days a week to his job. During the season Blumling has time to get a haircut only because there is a barbershop right next door to his subterranean office. When he gets a minute, he pounds on the wall. If a chair is open, the barbers pound back. He recruits continually the rest of the year. Ballplayers call him in the middle of the night. He studies game films, keeps index cards on opposing players and makes game plans. He also speaks to underwriters, undertakers, Knights of Columbus, Lions, Rotarians, Dapper Dans, blind groups and church groups. Like as not he will end with a plea for jobs “to keep our football players happy.”

As antidote to all this work Blumling has two relaxations. On Fridays, as often as he can, he takes his wife out dancing. This is for her benefit. And on Monday evenings he takes an hour out to bowl. Sometimes football pursues him even there. “I almost had a 300 one night,” Lou says. “I had just rolled strikes the first nine frames when some Ironman fan comes up. He says, ‘What’s the matter with your defensive secondary anyway?’ I was so mad I couldn’t even see the pins.”

“Before I married him, Lou sat me down and carefully explained what a coach’s life is like,” Mary Blumling says. She smiles wryly. “He was right,” she says. But she is intensely proud and intensely loyal, and so are her children. Predecessor Bob Snyder once mock-threateningly told Blumling’s boys that if the Ironmen lost their next game he would make their father, who was then defensive coach, eat the ball. One piped up, “You’re the head coach.”

Well before 6 p.m. on a typical Sunday, having most likely watched the Steelers on television a few hours before, the Ironmen begin arriving at their own dressing room, a poor place of peeling yellow paint underneath the east stands. You can call it a locker room, but there are no lockers: clothing and equipment are hung on nails and strewn on battleship-gray benches. The showers are in the same room, and the warm water vapor and naked bodies after a game give the scene a Dante’s Inferno quality.

As the team trots onto the field to warm up, the Magnolia High School Blue Eagles Marching Band of New Martinsville, or some other aggregation, strikes up the strains of some appropriate tune, such as On, Wisconsin . Somewhere in the stands a lone banner may read, SOCK IT TO ‘EM, IRONMEN. Some one of the seven or eight thousand spectators may wave a placard.

A very respectable number of boys will beg the Ironmen for autographs as they file back into the shabby dressing room. Fighting the acoustics, Blumling calls the men together for a last exhortation. (The room sounds the way it looks, which is like the inside of a cave.) A minute of silent prayer, and then the team runs onto the field again for introductions. The captains meet, the game is on.

It will be a crashing and bruising affair, on the ball and away from it. The passes are accurate and the receivers’ patterns complex. The jargon on the sideline is fully worthy of the NFL.

In the beery milieu of the Downs Club, where some Ironmen gather after home games, thoughts, if not talk, are directed to the next big-league tryout camps. An NFL scout—perhaps Jim Garrett of the Dallas Cowboys, himself a former CFL coach—will have been present and that is good news. Now they have been seen, their performances judged and they will be going to camp with a little bit of a rep. That is a little bit more than they had had before.

Big-league coaches are sometimes grown on farms, too. On a recent Monday evening Blumling was sitting over a beer in the kitchen of his old two-story frame house in the industrial suburb of Bellaire, Ohio when he was asked whether he, too, would like to “get a shot.” (Lou’s associates often hint that some year he may coach a team whose name’s reference is to some industry other than iron—like steel, for example, or oil or even meat-packing.)

He is eager to answer in one word. “Definitely,” he says, and the hunger shows. Then caution or modesty emerges. “In some capacity,” he says.

“It’s not that I’m anxious to be a big man. Even here, Mike Valan goes up to the country club, and that’s fine for him. His friends are up there. I stay down here where I belong. I don’t try to rise above my class.

“The main reason I want to make the big time is my wife. I’d like to give her some of the things she’s done without. In the past four years, if my wife had been the type to be a complainer or want this and that, I couldn’t have remained in this. A coach has to have a certain kind of woman.

“The club almost folded again this spring. That would have been bad trouble for me. I’d passed up a college job to take the Ironmen head coaching position, and it was too late to get another. Believe me, it had me worried. Here I sit with a wife and four kids and no job. You never know for sure whether the team is going to be here. You don’t know what kind of security you’re going to have for your family. But you don’t yourself mind, as long as it’s football.”

That was the end of the conversation, and it was now time for Lou Blumling’s weekly break from football, the bowling hour. He picked up a bag and strode out the screen door across the tiny backyard and down to the alley, where his kids were tossing around a football.

In a minute he was back, smiling sheepishly. With scarcely a word he set down the briefcase full of yellow cards with football diagrams and picked up the bowling bag instead. He grinned weakly and walked out again, looking preoccupied.